An ode to freelance historians

History of nations is written by the victors. History of napkins, perhaps less so.

I was born in a country that shouldn’t exist: a Central European state that couldn’t even be found on a map from 1795 to 1918, that served as the focal point of German Lebensraum between 1939 and 1945, and that was handed over to the Soviets right after the war — remaining under their heel for nearly half a century.

Contrary to how conquest is portrayed in fiction, for much of that time, the primary tool of the oppressors wasn’t violence: it was the control of monuments and history books. The invaders recast themselves as saviors, portrayed independence fighters as traitors, and established a new pantheon of heroes of the state.

The tail end of the Soviet regime overlapped with my childhood; this experience made me profoundly skeptical of all “big ticket” history — that is, the tales of great leaders and their movements. It’s not that the truth was unknowable, but the starting point was often a nation-building myth. Your neighbors across the border, your political opponents, or even some ethnic minorities in your country could have a version of the same events that’s diametrically opposed to yours.

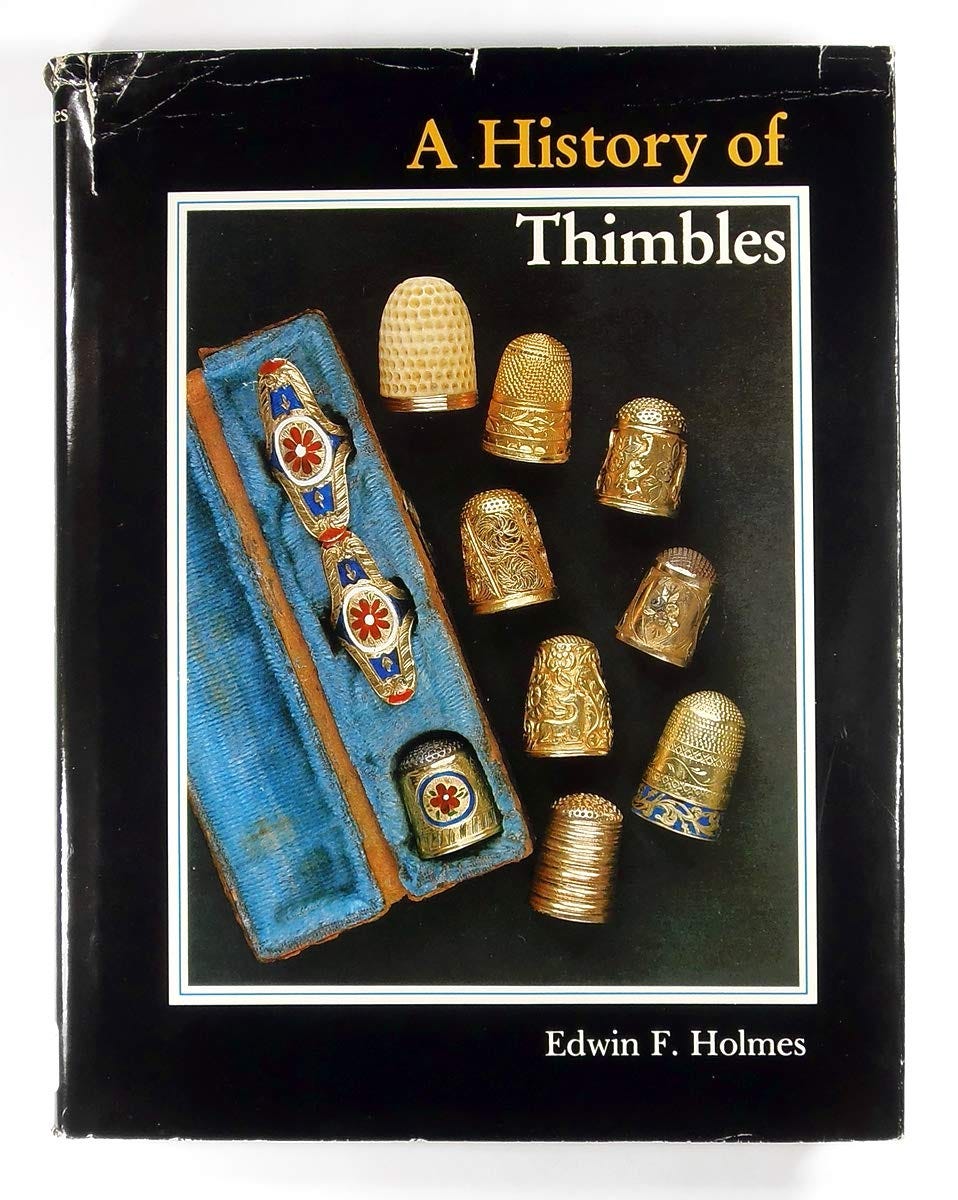

In a world of big patriotic myths, I found it rewarding to instead study the history of small things. As it turns out, the annals of pencil manufacturing or coffee trade tell you a lot about industrial progress, global trade, wealth, and societal change throughout centuries. At the same time, the topics are unglamorous enough to keep the blowhards out.

This brings me to a group that holds a special place in my heart: an army of part-time, freelance historians who zero in on obscure topics, obsessively research them, and then share the findings with the world. There are countless examples. We have a cipher machine museum and a whole website dedicated to early Hungarian firearms. We have an old calculator gallery, chronicling a century of remarkable technological advances and corporate rivalry. We have a webpage dedicated to early office life. There’s a person documenting flea circus history. And to toot my own horn, you’d be surprised what you can learn from weird banknotes and giveaway comics published in the 1950s.

Eccentric collectors and archivists existed long before the internet, but they had very little reach; at best, the collections served as local curiosities. If the person had a penchant for writing, they could perhaps publish a book — and reach dozens of readers nationwide.

The internet changed all this. Nowadays, if you want to research the taxonomy of vacuum tubes or learn about that weird foot bridge in Minnesota, the knowledge is just a click away — although like much of the “hobby” web, such gems are increasingly buried below commercial websites, tepid Wikipedia summaries, and SEO spam.

With less and less traffic, many of these sites won’t stand the test of time. I know of a major catalog of early European militaria that disappeared off the internet shortly after the death of its author. No wonder; if you run a hobby website that gets a hundred visits a day, would your heirs remember to pay the hosting bill?

It’s a bummer that we’re not making a concerted effort to catalog and preserve this knowledge; perhaps webrings are due for a comeback?

👉 For a thematic catalog of articles on this blog, click here.

You may find interesting that this kind of history is not just "freelance history". There's a specific field of research, started from the Italian historian Carlo Ginzburg, which is entirely devoted to explain small things in order to change our understanding of the big picture: https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Microhistory

This article resonates with me, as I come from a similar background, and am one of those obscure historians (WW2 radio gear). I like how you've set the stage and described the value.