Some notes on influencering

The ups and downs of publishing non-commercial content on the internet.

I’ve been putting content on the internet for all of my adult life. The works ranged from security research, to open-source projects, to long-term writing on a variety of topics. In an earlier article, I extolled the virtues of publishing just for the sake of it:

“The concepts in our heads are nebulous and ever-shifting. Putting them on paper forces us to pressure-test our assumptions and address gaps.

You don’t need to be the world’s leading expert to write about a particular topic. Experts are often busy and struggle to explain concepts in an accessible way. You should be honest with yourself and with your readers about what you know and don’t know — but otherwise, it’s OK to write about what excites you, and to do it as you learn.”

For over two decades, I resisted the desire to monetize my side projects. Part of this was pragmatic: my daytime job paid better than what I could realistically make by cramming ads into articles or selling geeky books. But just as important, I didn’t want to turn a hobby into yet another chore.

Today, I’d like to share some of the less obvious takeaways from the journey so far.

#1: It’s still a chore!

By refusing to monetize, you give up most of the tangible upsides of online publishing; the downsides stay with you either way. In the long haul, you should expect to spend as much time putting out fires and wrangling the technology as you spend on creative pursuits.

To give you a taste, I had my website randomly delisted by Google, hijacked by SEO spammers in Bing, repeatedly flagged by antivirus tools, and hit with bogus abuse and copyright claims. In each case, it took weeks to get it sorted out, often having to lean on informal connections to get through. I recently noticed that the fourth most popular article on this Substack appears to have been banished from Google. Why? Who knows…

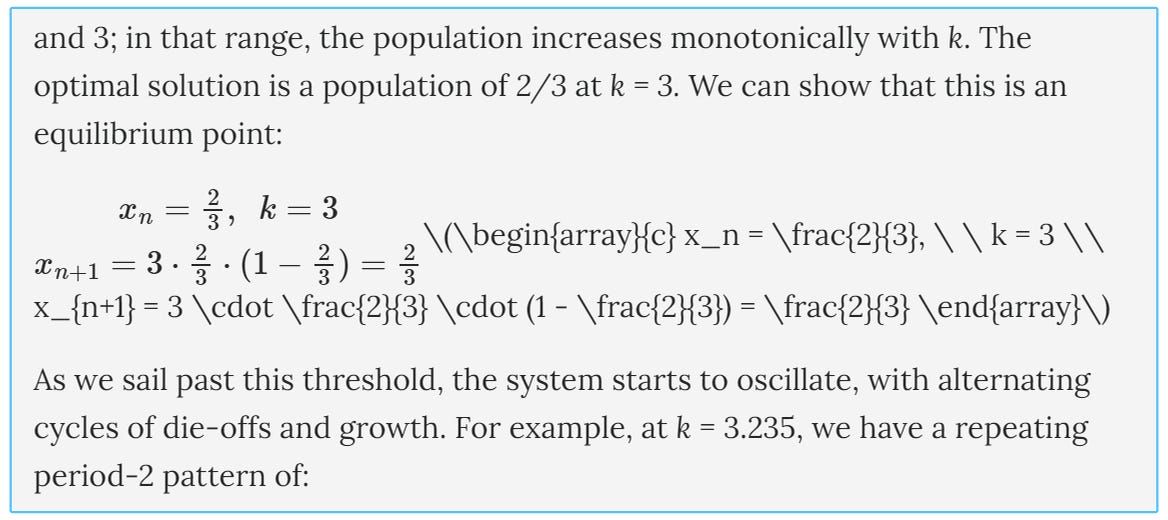

When I self-hosted, I had to deal with endless configuration and maintenance tasks — and at one point, an outright server compromise. Third-party hosting is easier until it isn’t. For example, it took me nearly a year to get this rendering issue fixed by Substack:

Their support was of no help; what finally worked was a “cold” email to one of the site’s founders. In other words, it took perseverance, luck, and some skill.

Even with free hosting, your costs add up pretty quick. I poured thousands of dollars into my projects, and I’m sure the same goes for most other habitual content producers you come across. The expenses range from photo and video gear, to software licenses, to the procurement of antique calculating machines and random PCBs.

#2: There are weirdos on the internet

Unless you’re a pop star, you are unlikely to gain devoted fans who follow you around. Most of the time, when we come across helpful content on the internet, we don’t think much of the stranger who put it out there. We just take the experience for granted and move on.

Online hate isn’t so fleeting. Sooner or later, you come across a heckler who follows you around and makes it their life’s mission to “debunk” your claims — or simply hurl insults or creepy remarks in your general direction without any pretense of constructive criticism.

This seems worse than it really is. Threatening or putting down others on the internet is a pretty miserable hobby, often just a way for the other person to cope with insecurities and stress. But still, early on, it plays tricks on you: what if I have it coming? What if I’m really as clueless as they say?

#3: Indifference is the real killer

If your content upsets another person, it still means you have an audience. More often than not, the controversy pulls in bystanders and lets them make up their own minds. There is such a thing as bad press, but on the internet, the threshold is pretty high.

What stings far more is when you get no reaction whatsoever: all of sudden, the content’s most important raison d'être is lost. Few bloggers or vloggers quit because of the occasional snide remark; many give up when their metrics don’t budge post after post.

The process of building an online audience is slow and unpredictable, so my best advice is to pick a platform that doesn’t rub your nose in it. I’ve previously written about my special dislike of YouTube, where the entire creator experience revolves around view counts:

“The complexity of the medium is not YouTube’s fault. What I fault them for, however, is that they deliberately thrust authors into a global popularity contest — and offer no reprieve. You can use Reddit, Twitter, or Facebook to hang out with friends without knowing who’s the highest-ranking influencer of the week. On YouTube, view counts are all there is — inescapable and in-your-face.

[A thumbnail of a woman flipping off an Alaskan malamute, 82M views]

Even in the privacy of your own channel, you’re being compared: to the right of your video, you see similar clips from strangers, along with their scores. The takeaway is simple: there must be something wrong with you if you can’t compete with a person flipping off their dog.”

#4: Follower counts are a lie

Most social media platforms use algorithmic feeds — that is, they decide what to show not based on their users’ explicit preferences, but on what’s most likely to elicit a response and keep the user engaged. Because of this, follower counts are fairly meaningless: just because a person follows you on Instagram or Facebook, it doesn’t mean they will ever see your posts.

To be fair, the platform you’re reading this on — Substack — is a bit of an outlier. They deliver every post via email, so if a subscriber is still alive and the mails are not ending up in spam, they will see what you have to say. But for a more typical data point, let’s have a look at Twitter: I have 35k+ followers over there, but this translates to just about 1,000 to 2,000 impressions on a typical post, and then maybe 60 link clicks (~0.2%). YouTube is the same: I don’t use it much, but I notionally have 1,100 followers on the site — yet a video that isn’t promoted elsewhere tends to get 50-100 views.

I’m not sure there’s any special takeaway to this — except, if you want to build an audience around subscriptions, make sure they are real. And don’t assume that people with 100k or 1M followers have anything resembling that kind of reach.

#5: Money is the root of only some evil

If you ask an average person what’s corrupting the internet, they will probably point to monetization. But it’s not just about money; non-commercial content creators are dealing with comically distorted incentives too.

For example, did you know that my Substack audience is telling me to stop writing? It’s true: whenever I post a new article, I reliably lose subscribers. If you have a sufficiently large audience, there’s always someone who expected something different, so your new post nudges them to finally unsubscribe. But when I’m not posting, I quickly make up the losses with sign-ups driven through Google search. Clearly, the best growth strategy is to post nothing at all.

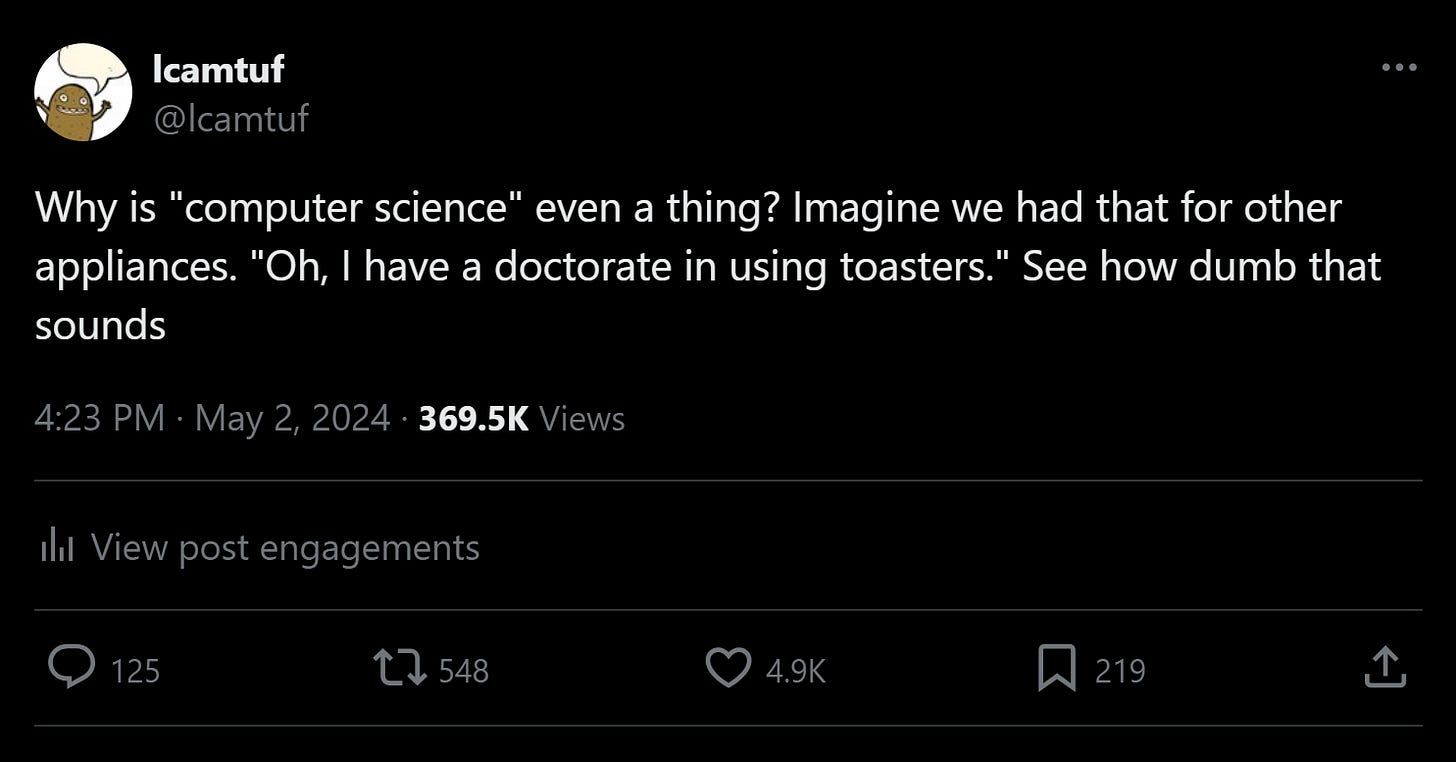

More seriously, the sheer randomness of internet’s attention, and its heavy bias toward low-effort content, will drive you nuts. Some of my most popular posts are throwaway quips and memes that went viral on social media. One of my life’s crowning achievements is this:

In contrast, some of the work I put weeks or months into ended up losing the SEO game and getting nearly zero traffic. A while ago, I put together an impassioned, contrarian guide to photography, illustrated with a number of interactive shots. The only traffic it’s getting today are confused searches for a porn performer with a vaguely similar name. Even though I don’t write for money, there is an immense pressure to produce clickbait — even if simply to add “hey, since you’re here, check out this serious thing”.

👉 For a categorized list of posts on this Substack, click here.

Let's try (again) to make the Internet more romantic and less cynical.

You can still access the knowledge for free (ISP fee aside). There are people on the Internet who share their knowledge for free (I try to do this myself, although I could probably do more). This is how it all started in BBS, early www and usenet, ZINs, open source, free tool sharing, forums and all kinds of communities. People decide to contribute content to the web for something other than money – whether it's idealism or exhibitionism. Well, to be honest, there was a time when there was no money on the Internet, or there was very little of it, so it was easier to make a decision, but the argument remains. In any case, easily accessible, free content was the fuel for the development of the Internet at all levels of the evolutionary ladder, from people to corporations. For us, ordinary mortals, free information provided a low barrier to entry into any topic (see your recent article about strange topics on the Internet).

Please write more, share your knowledge for free. This rapidly changes our fate, from consumers of culture to producers. We become artists of sorts. It sounds crazy, but it's true. Ignore everything else, it's manageable. Otherwise, you'll be just another blogger who shares their unique and great guide or tool for a small fee. Nobody will buy it. Sales is governed by different laws than science. We don't need salespeople, we have plenty of them everywhere. We need evangelists of ideas and freedom.

Michał, I have been following your activity for probably over 20 years. Thank you for posting content online for free. Please continue.

wow, my comment turned into a rant in favor of publishing free content online. I'm not writing this because I'm trying to convince you or your readers, but I think, well, I need to rant in favor of publishing free content online. Oh, the irony.

I doubt you posted this to get warm fuzzy feedback, but I've been loosely following you since the guerilla guide to CNC days and I appreciate your work and all the random topics.

I also find myself liking substack as a platform quite a bit more than any of the other social media.