Why are sine waves so common?

A simple question that takes some effort to answer in a satisfying way.

Sine waves tend to crop up everywhere you look. They can be observed on the surface of water, in the motion of a pendulum, in electromagnetic waves, and in the behavior of simple electronic circuits. But… why?

The most common answer on the internet is “because sine waves are generated by rotating circles”. This is not wrong, but it doesn’t tell us much: after all, there’s no rotating circle in a lake; you also won’t find one in a capacitor or an inductor. Another common claim is that “sine waves are generated by simple harmonic motion”. Once again, this is technically correct, but it doesn’t really say why.

In today’s article, let’s try to answer the question in a more thorough way. We’ll go on a quick romp through Newtonian physics; many of us work hard to forget it all after finishing school, but I promise to make it reasonably fun. And there will be no test at the end of the article!

Simple harmonic motion

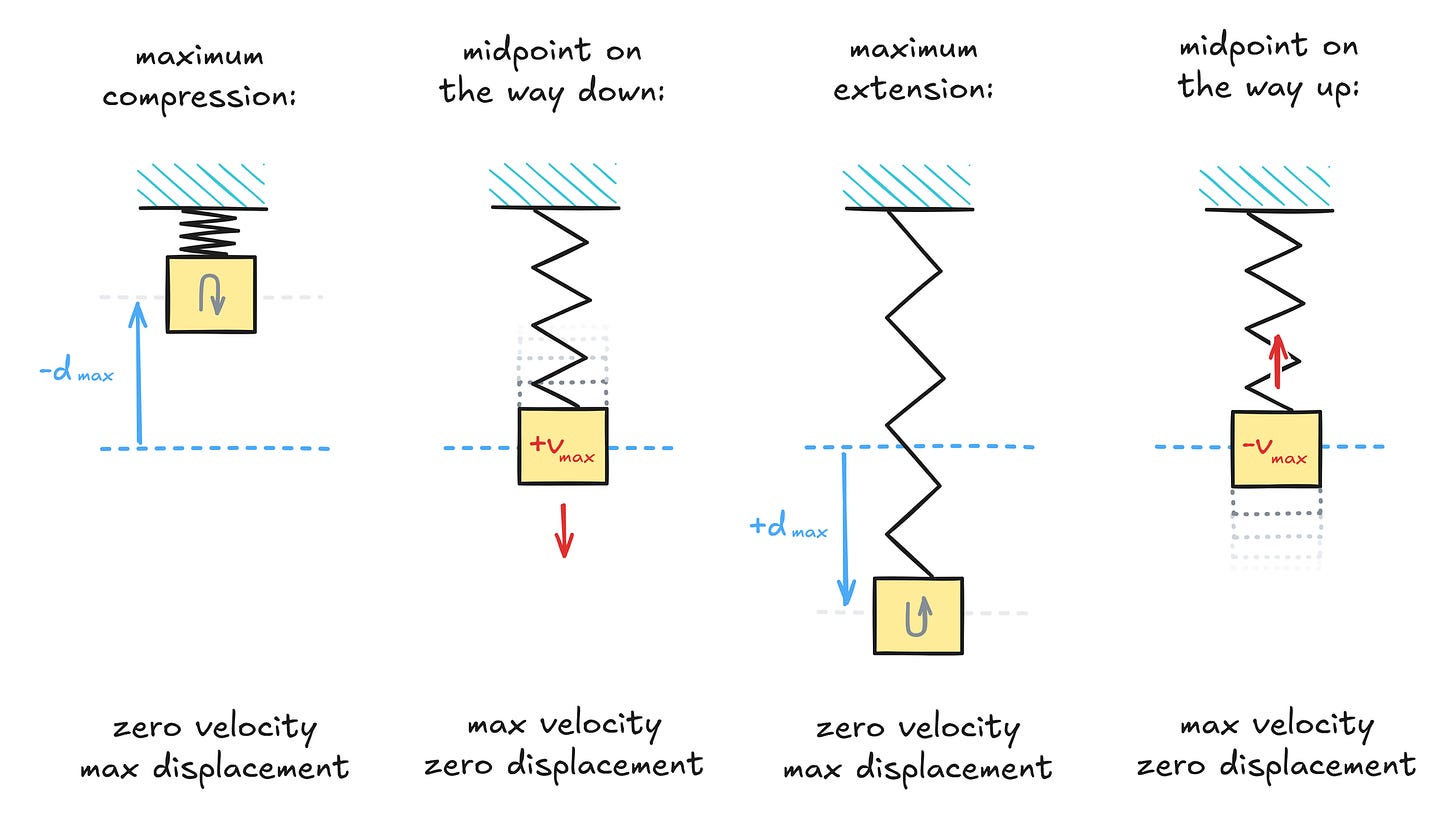

Let’s start with the most rudimentary mechanical oscillator: a mass suspended on a spring. We assume that the spring is perfectly elastic and there is no air drag — so if you give it a push, it should be merrily bouncing for all eternity:

In the diagram, we can spot two interesting boundary conditions. The first one occurs when the spring being maximally compressed or extended; at that point, the velocity of the block is zero and it’s about to reverse direction. The other boundary is reached when spring tension drops to zero at midpoint of the oscillation. At that moment, the block stops being pushed — i.e., accelerated — so this corresponds to its peak velocity.

Note that the description above neglects gravity. For simplicity, we can add “in space!” to the description of the experiment, but informally: gravity doesn’t change the overall dynamics. It’s a constant force acting on the mass, so it just shifts the midpoint condition from “the spring exerts no net force” to “the spring exerts force exactly opposite to gravity”. The block still swings symmetrically from that new midpoint.

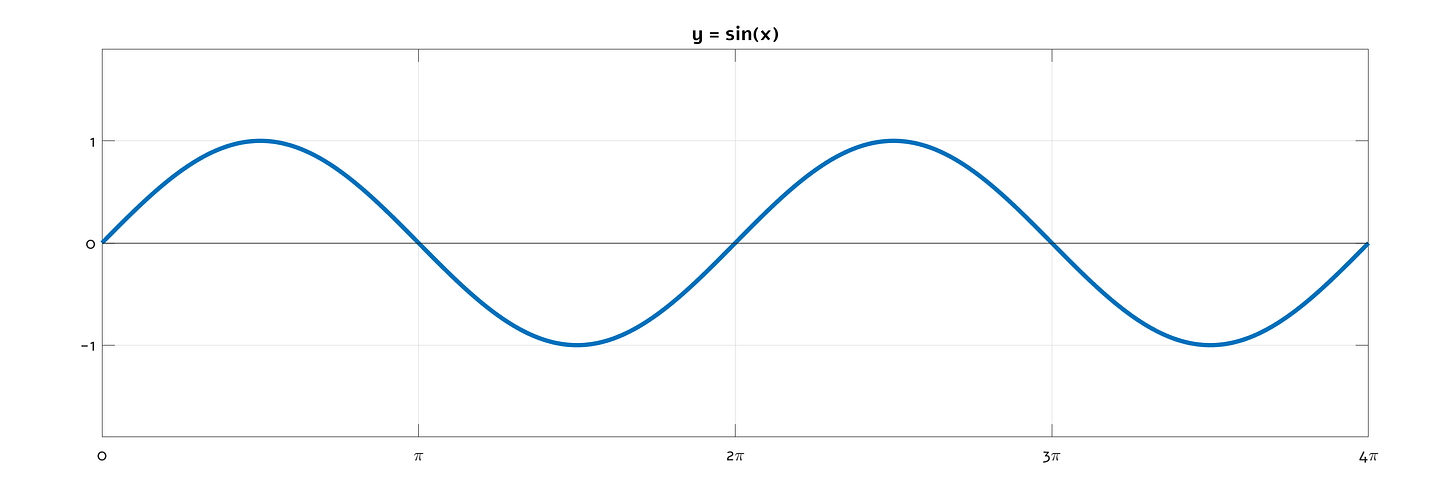

In any case, yep: if you plot displacement of the spring (d) or speed of the block (v) over time, the result will be a sinusoid. But don’t settle for that answer — we still haven’t answered why!

To understand what’s going on, we need to bring up an important yet simple concept in physics: the conservation of energy. In essence, in a closed (i.e., isolated) system, energy can change form — say, from mechanical energy to heat — but the sum of all its forms must remain constant over time.

In this particular experiment, the system is alternating between potential energy stored in a spring and kinetic energy of a moving block. And at all times, the oscillator must adhere to the following rule:

This equation deals with energy, but that’s not something we can directly observe. We can measure spring deflection and block velocity, but we don’t know how these quantities relate to energy — and even if we peek at Wikipedia, it won’t tell us why.

Energy stored in a spring

The empirical model of a spring is pretty simple: it’s just a linear device that pushes back proportionally to how much you compressed it so far.

More precisely, the momentary “pushback” force you need to overcome (F) to keep compressing the spring is a function of previous displacement (d) and a spring-specific stiffness factor k:

The value of k depends on the material the spring is made from and its exact shape; for our purposes, we can just assume that it’s some arbitrary constant. If we plot the equation, it’s probably no surprise that we get a straight line:

Let’s think about what happens if we compress the spring d = 0 to dmax. From the formula above, we know that the force we need to overcome will gradually ramp up from F = 0 to F = k × dmax.

When dealing with a simple linear ramp, we can intuit without calculus that the average force we’ve been pushing with is equal to the midpoint of the graph, i.e.:

But how does force correspond to energy?

Energy is related to work. If you’re leaning against a stationary lawnmower, you’re exerting force, but no energy is being transferred — and thus, no work is getting done. If you start pushing the lawnmower up a hill by applying a constant force to the handlebars, the situation changes. The amount of work performed — i.e., the amount of energy (E) you expended — is equal to the applied force times the distance traveled (d):

This also works for pushing a spring! We applied an average force of Favg to compress the spring by some distance dmax. Combining the formulas, we get:

Neat: this gives us the potential energy stored in our spring.

Energy of a moving mass

The case of a spring was fairly intuitive; the physics of a moving mass are harder to grok, but we can cheat by bringing up the conservation of energy once more. The trick is that the energy of a moving object must be the same as the energy we transferred to it to accelerate it to that speed.

In other words, if we have a block with a constant mass m, we just need to see how much effort it would take to get it from v = 0 to some given vmax. We can accelerate the object any way we like; two identical objects accelerated in different ways but traveling at the same speed still have the same kinetic energy.

For simplicity, let’s say that we ramped up the speed at a linear rate within t = 1 second. Acceleration is just the increase in speed over time, so in this case, the equation is:

Because we ramped up the speed in a straight line from 0 to vmax, it once again follows that the average speed in that one-second time window is:

We can now trivially calculate the distance traveled by the mass while being accelerated (d) by multiplying the average speed by the duration of the push:

From Newton’s laws of motion, the acceleration of an object is proportional to the applied force and inversely proportional to mass (a = F/m): in space, a rocket with a constant thrust will be gaining speed at a constant rate for as long as the fuel lasts. We can rearrange this dependency to solve for force:

Substituting the previously-calculated value of a, we get:

So far, in our toy scenario of trying to accelerate an object any way we like, we calculated the constant force pushing the object (F) and the distance traveled (d). To figure out the work done — and thus, the kinetic energy imparted on the object — we can just plug it into the earlier formula for work (W = F × d):

We end up with an expression for kinetic energy that depends only on speed and mass.

Right… why are we doing this again?

That’s the neat part. Now, we can rewrite the earlier equation for the conservation of energy as:

I split out the k/2 and m/2 terms on purpose: they’re just material-specific constants that scale d and v in their respective axes when we plot the observed state of the system. To keep the math tidy, let’s assume that by some stroke of luck, the constants worked out to 1, leaving us with this simplified energy formula:

We can also ignore the units altogether and rewrite the equation in a way that relates the numerical values of displacement and speed:

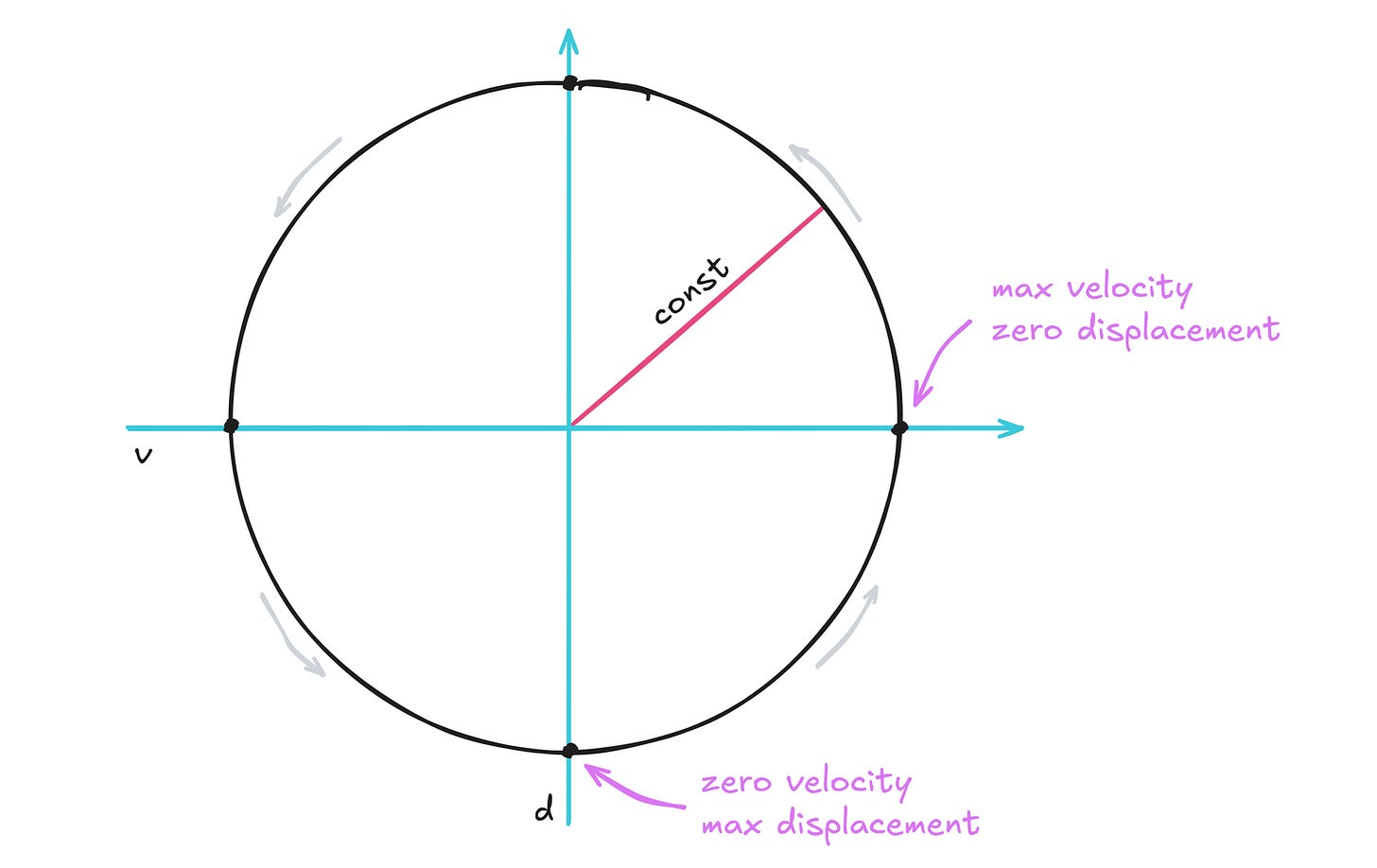

What does this mean in practice? Well, let’s use Cartesian coordinates to plot some arbitrary system state — a randomly-chosen combo of block speed (v) and spring deflection (d):

We know the values of d and v — we picked them! — but I also added a segment labeled x. It’s the distance from the origin of the coordinate system — (0, 0) — to the point representing system state at (v, d).

The value of x can be calculated from the Pythagorean theorem:

Note the similarity of this expression to the earlier condition for the conservation of energy:

If the criteria for the conservation of energy in this system is that the sum of these squares (d² + v²) must be constant, then x² must be constant too! And if x² is constant, then it follows that x must be a (different) constant value.

This is an important revelation. It means that all pairs of (v, d) values in a mass-on-a-spring system that obeys the law of conservation of energy must be equidistant to (0, 0). And the set of these equidistant points is… you guessed it, a circle:

So, the observable state of our mass-on-a-spring contraption does travel around the circumference of a circle; the circle is just hidden really well.

The rest is mostly triangles

If you already know why circular motion would produce a sinusoid, feel free to skip ahead. If not, let’s cover it briefly. The most basic introduction to trigonometric functions is usually done in terms of the relationship between the sides of a right-angle triangle:

But if the hypotenuse is chosen to have a constant length of 1 and if we anchor one end to the center of the coordinate system, then the far end draws a circle with a radius of 1 as the value of a progresses from 0 to 360°:

Recall that the value of sin(a) is equal to the length of the opposite (vertical) edge divided by the length of the hypotenuse. Here, the hypotenuse has a length of 1, so the the the length of vertical edge is just equal to sin(a), and the length of that edge maps to the vertical coordinate of point A.

In our earlier model, a point traveling along a circle was used to describe the state of the system; the vertical coordinate represented deflection and the horizontal coordinate represented speed. In effect, we could rewrite it in terms of trigonometric functions of some angular timing variable t:

But is it constant speed?

“Hold on”, some readers said, “how do we know that the speed at which the system advances along the circle is constant?”. That’s a good point: if the system is traveling around the circle in some sort of a choppy pattern, the plots of speed over time or displacement over time wouldn’t be pure sines. Constant speed feels like the most logical answer, but we shouldn’t leave this up to feels.

A rigorous explanation is relatively hard to pull off without leaning on prior knowledge of calculus, but one of the readers suggested the following geometric approach that’s pretty easy to grasp:

The circle on the left is the earlier visualization of system state, with the horizontal axis representing block speed and vertical axis representing spring displacement.

On the panel on the right, we take a look at the evolution of the system in a vanishingly small time slice (Δt). As in some of the earlier articles, I don’t want to bring in all the formal baggage of mathematical analysis, but there are two roughly equivalent ways to think about this scenario: as a dynamic process where the time slice tends to zero and we’re making inferences about where the value seems to be ultimately headed; or as a static snapshot where the increment is an infinitely small (infinitesimal) quantity.

Either way, on a sufficiently microscopic scale — when Δt approaches zero and we need humongous zoom to observe the change in system state — we can view the local segment of the circle as a straight line.

The fundamental question we’re trying to answer is whether the incremental distance traveled along the circle (Δs) depends in some way on the momentary value of v or d — or if it’s just a function of time.

Looking at the small shaded triangle on the right, we can apply the Pythagorean theorem and say the following:

So far, so good. Next, let’s ponder what Δd actually is: it’s the increase in displacement in our tiny time slice. And what physical quantity describes the change in position over time? It’s speed! The incremental displacement of the block — and thus the spring — is proportional to the momentary speed, v, and the duration of motion:

We know that v gradually changes over time – but if Δt approaches zero, we can informally assert that the change in this time slice is of no consequence because v is necessarily changing only by an infinitesimal amount.

Anyway: the interesting insight is that Δv has a similar relationship to d as Δd has to v. This is a bit less obvious, but let’s start with the intuitive part: the increase in speed is proportional to acceleration and time (Δv = a × Δt).

Further, as discussed previously, acceleration of the block is directly proportional to applied force (a = F/m); and spring “pushback” force that’s acting on the block is directly proportional to overall displacement (F = k × d). In essence, combining the formulas we talked about earlier in the article, we arrive at:

Both k and m are just scaling constants that squish or stretch the circle; for simplicity, we opted to assume they work out to the same numerical value, so the simplified formula boils down to:

Now, we can plug these formulas for Δv and Δd into the earlier Pythagorean formula for the small, shaded triangle:

Equipped with a formula for Δs, we can divide it by the duration of the time slice (Δt) to calculate the speed at which the system travels along the circle. To avoid confusion with earlier variables, I’m going to call this u:

Recall that the main thrust of our earlier proof for “circularity” was that v² + d² = const. So, for any combination of v and d, the momentary speed along the “state circle” is the same. QED.

That’s a lot of effort to analyze a whimsical scenario, but many other natural phenomena have a similar relationship between the observable state and internal energy - and exhibit similar dependencies between rates of change for interdependent quantities. For example, the basic model of a capacitor is mathematically identical to that of a spring: the more charge you store, the harder it is to add another electron. Similarly, an inductor resists the change in current in a way that’s nearly identical to how a mass reacts to being accelerated or slowed down.

👉 For a bit more basic physics nerdery, check out the articles on the physics of conduction, the behavior of transistors, and on core concepts in electronic circuits. For the best damn intro to the discrete Fourier transform, click here. For more trigonometric tricks for calculating Vrms, try this article.

I write well-researched, original articles about geek culture, electronic circuit design, and more. If you like the content, please subscribe. It’s increasingly difficult to stay in touch with readers via social media; my typical post on X is shown to less than 5% of my followers and gets a ~0.2% clickthrough rate.

... which of course raises the question of "But why sine waves in particular?"

There are infinitely many possible pairs of curves that trace out a circle, and it's not obvious why the angle should increase linearly when the force from the spring isn't constant.

But, it's not that hard to show why this happens: (still assuming k and m are 1 for simplicity)

On our circle, the x-axis is velocity, which is how fast the displacement changes, or how fast the system is moving along the y-axis.

The y-axis, displacement, per F=k*d, is the acceleration, or how fast the velocity changes and how fast the system is moving along the x-axis.

From here, we can apply some Pythagoras to find that the rate the system moves away from a point is sqrt(x^2 + y^2), which is the same as the distance of that point from the center of the circle. But on a circle, all points are the same distance from the center. Therefore, the angular velocity must be constant -- yielding sinusoids.

The math-y explanation is that "the derivative/integral of a sinusoid is a sinusoid", so it arises when a variable is linearly, but indirectly effecting itself. Like how position affects spring force (linear), which affects velocity acceleration (integral), which comes back to position (integral). If you want to be precise, each integration/differentiation introduces a 90° phase shift, and the reverse direction of the spring's force introduces a 180° shift: 180° + 90° + 90° = 360°, so the overall effect is to keep the weight moving on a sinusoid.

There's a nice geometric explanation of the calculus in one of the electronics articles: https://lcamtuf.substack.com/p/primer-core-concepts-in-electronic

The math graphics erroneously render d^2+v^2 as "d^2v^2" implying multiplication where there should be summation, starting somewhere around total energy summation